Page 119 - kpi18886

P. 119

111

until 2016, soon extended to 2026. A ban on additional zones beyond

the original fourteen was similarly bypassed by a provision enabling the

creation of “sub-zones.” These sub-zones numbered only 41 in 2000, a

number that increased to 267 in 2010, encompassing 350 municipalities

that are co-owners with governments, banks, and agencies, especially

national industrial development offices, of approximately 80% of the

zones. This type of blended central, regional, and municipal governance

has contributed substantially to the considerable success of Polish

zones, which have been further enhanced by the rise of clusters in the

past ten years. This pattern of vibrant development has been dominated

by certain sectors, most notably the automobile industry, which

accounts for 42% of total investments in the zones. Total investment

between 2005 and 2011 came to 85 million euros, with foreign

7

investments rising to 82%, nearly half of Asian (Japan and Korea) or

American origin.

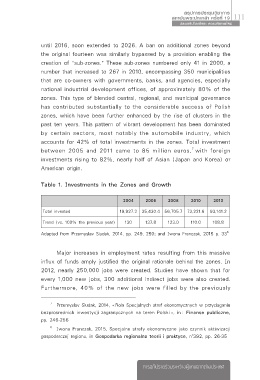

Table 1. Investments in the Zones and Growth

2004 2006 2008 2010 2013

Total invested 19,927.2 35,430.4 56,705.7 73,221.6 93,141.2

Trend (vs. 100% the previous year) 130 137.8 123.0 110.0 108.8

Adapted from Przemyslav Siudak, 2014, pp. 249, 250; and Iwona Franczak, 2015 p. 33 8

Major increases in employment rates resulting from this massive

influx of funds amply justified the original rationale behind the zones. In

2012, nearly 250,000 jobs were created. Studies have shown that for

every 1,000 new jobs, 300 additional indirect jobs were also created.

Furthermore, 40% of the new jobs were filled by the previously

7 Przemyslav Siudak, 2014, « Rola Specjalnych stref ekonomycznych w przyciaganiu

bezprosrednich inwestycji zagranycznych na teren Polski », in : Finanse publiczne,

pp. 246-256

8 Iwona Franczak, 2015, Specjalne strefy ekonomyczne jako czynnik aktiwizacji

gospodarczej regionu, in Gospodarka regionalna teorii i praktyce, n 392, pp. 26-35

o

การอภิปรายรวมระหวางผูแทนจากตางประเทศ